Igreja da Ordem Terceira de Nossa Senhora do Carmo

Introduction

The Igreja da Ordem Terceira de Nossa Senhora do Carmo in Tavira is a Baroque landmark, still alive with faith and history. Built by local hands in the eighteenth century, this Roman Catholic church reveals Tavira’s devotion, artistry, and evolving sense of community. Today, we can step inside the Carmo church and discover gilded altars, painted ceilings, and stories that connect past and present in the heart of the Algarve.

Historic Highlights

⛪ Founding Moments: Lay Brotherhood and New Beginnings

The Igreja da Ordem Terceira de Nossa Senhora do Carmo in Tavira began as a project of local laypeople in the early 18th century. The Venerable Third Order of Carmo, desiring their own space apart from the Franciscans, set their sights on land near the Ermida de São Brás. Through notarial deeds in 1737, Tavira’s citizens formalized a land gift, revealing the depth of communal spirit shaping this Roman monument.

“The Senate voted to consecrate an altar to Pax Augusta… in the Campus Martius.”

— Augustus, Res Gestae

🎨 Baroque-Rococo Flourish: Architecture and Art

By 1744, construction of the triumphal church was underway, fueled by donations from Third Order members and local benefactors. The main church structure reached completion in the 1750s—even hosting the distinguished Bishop Inácio de Santa Teresa’s burial in 1751. Outside, visitors admire a late Portuguese Baroque facade, with cut-stone pilasters, curving pediment, and evocative azulejo tiles depicting Nossa Senhora do Carmo. Instead of twin bell towers, Tavira’s Carmo features a single espadaña (belfry), a choice born from both taste and practical means.

“The facade was finally finished in 1792, as marked on its stone frontispiece.”

— Arquivo Histórico Municipal de Tavira

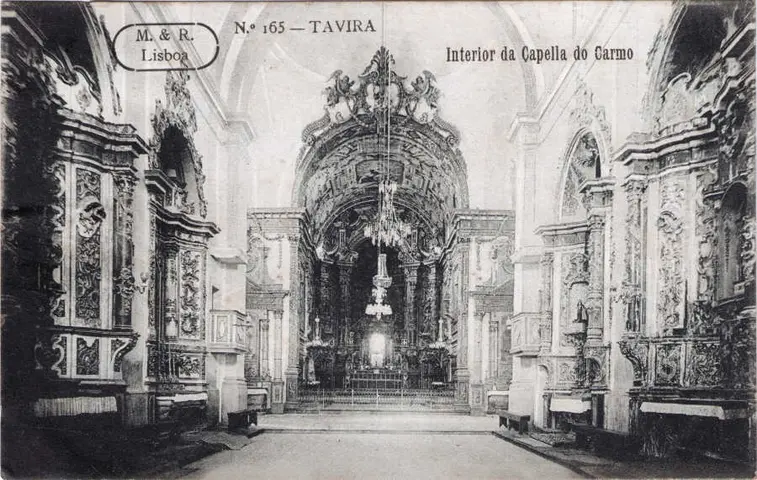

🧑🎨 An Artistic Sanctuary

Step inside, and the church’s Latin cross plan and gilded altarpieces shine with local craftsmanship. Polychrome carvings and illusionistic ceiling paintings invite us to imagine the 18th-century devotion of artisans. Each side chapel, dedicated to Carmelite saints like St. Elijah or St. Teresa of Ávila, tells a story of faith and artistry. The main altar, with its Rococo carvings and image of Our Lady of Carmo, still inspires awe. Local legend holds that fishermen’s families once lit candles before her statue, seeking protection on stormy seas.

⚔️ Anecdotes, Rivalries, and Living Traditions

The church’s history isn’t without drama. In 1787, a competitive dispute arose between Carmelite and Franciscan lay communities—one party skipped a key procession, leading to symbolic torn agreements and heated words. Tavira’s Carmo became the focal point for such local rivalries, yet also for festive processions and feasts, especially on July 16th, when the community gathers to honor Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Whispered tales recall Bishop Inácio’s ‘ghost’ sometimes glimpsed near the chancel after dark.

🔄 Adaptation and Preservation

After the suppression of religious orders in 1834, the convent changed hands, and the Third Order faced declining membership. Yet, the church endured, celebrating weddings, masses, and cultural events. Recent decades brought new life: the former convent wing now houses Tavira’s Ciência Viva science center, while the municipality stewards preservation of sacred art. This dynamic blend of old and new ensures the Carmo church continues serving both heritage visitors and the devout.

💡 Visitor Tip

Pair your visit to the Carmo church with the nearby Tavira Ciência Viva Center in the former convent—exploring history, faith, and science all in one inspiring place.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- Early 18th century – Third Order of Carmo lay brotherhood established, tied to Convent of São Paulo.

- 1737 – Notarial deeds record land donation for new Carmo church and convent in Tavira.

- 1744–1745 – Construction begins on the Igreja da Ordem Terceira de Nossa Senhora do Carmo.

- 1751 – Bishop Inácio de Santa Teresa is interred in the church; main structure is complete.

- 1792 – Facade finished; date inscribed on church’s frontispiece.

- 1834 – Suppression of religious orders; Carmo complex nationalized and sold to private owner (1835).

- 1921 – Third Order cedes administrative rights to Faro district.

- 1996 – Municipality of Tavira acquires site, ensuring preservation and public access.

- 2012 – Church and annex designated Monumento de Interesse Público.

- 2005–present – Former convent wing houses Tavira Ciência Viva Center and community groups.

Social Origins and Lay Engagement

Unlike religious orders comprised only of clergy or monastics, the Carmo church in Tavira was conceived by laypeople driven by personal devotion and a desire for communal distinction. Early records in the Arquivo Histórico Municipal de Tavira reveal the complicated negotiation between Carmelite friars, local authorities, and Tavira’s Franciscan community over church autonomy and land use. The strong involvement of artisans, merchants, and notable families resulted in a collaborative ecosystem: locals funded physical construction, sponsored altarpieces, and formed the backbone of the Carmelite Third Order. Church membership also provided tangible benefits, such as burial rights and spiritual privileges—reflecting how religious spaces operated as centers for social and civic organization in 18th-century Portugal.

Baroque-Rococo Artistry: Regional Adaptation

The Igreja da Ordem Terceira de Nossa Senhora do Carmo is a regional exemplar of late Portuguese Baroque aesthetics, gradually incorporating Rococo influences as seen in its playful facade curves and gilded interior decoration. Unlike metropolitan churches with larger budgets or Brazilian patronage, Tavira’s Carmo adapted the Baroque style to local taste and capability. The distinctive single belfry (espadaña) and absence of elaborate twin towers highlight both resource limitations and regional interpretation. Master carvers and local artists contributed to the nave’s woodwork, painted ceilings, and intricate retables, showcasing the Algarve’s religious artistry during Portugal’s economic and intellectual recovery after the 1755 earthquake.

Conflict, Folklore, and Civic Identity

The church’s history is deeply entwined with Tavira’s local politics and oral tradition. The 1787 rivalry between Carmelite and Franciscan lay fraternities over procession rights illustrates how parish churches played out the negotiations of status, precedence, and ritual belonging. These ‘small-scale’ conflicts, recorded in period documents, helped shape the town’s broader civic identity. Furthermore, burial of prominent figures—such as Bishop Inácio de Santa Teresa—signals the Carmo’s early prestige and the way religious spaces acted as repositories of collective memory. Folkloric accounts of the bishop’s restless ghost or fishermen’s candle-lit prayers reveal the continued power of the Carmo church in popular imagination, blending sacred history with lived experience.

Secularization, Loss, and Adaptive Reuse

The Liberal Reforms of the 1830s triggered a disintegration of monastic life across Portugal. The suppression of religious orders meant the Carmo convent was quickly privatized; the lay Third Order soon lost influence as membership dwindled. Yet, the church survived as a space for worship, adapting to shifts in ownership. The 20th and 21st centuries brought new forms of heritage stewardship: municipal acquisition, state designation as a protected monument, and the innovative repurposing of the convent annex for Tavira’s Ciência Viva Center and community groups. This adaptive reuse reflects both the resilience and flexibility of historic sites to serve contemporary needs while maintaining layered identities.

Comparative and National Significance

The Carmo church in Tavira forms part of a wider architectural and devotional tradition seen in Algarve (e.g., Igreja do Carmo in Faro) and northern Portugal (e.g., Porto’s Igreja do Carmo). Each site blends Baroque-Rococo style, Carmelite iconography, and lay-driven heritage. What sets Tavira’s example apart is its dual use: a sacred space preserved for worship, and a former convent repurposed for science and civic activity. This balance between conservation and innovation demonstrates an effective heritage management model, serving as a reference point for similar sites across Portugal. Municipal and heritage authorities—such as the Direção Regional de Cultura do Algarve—play a key role in negotiating this delicate stewardship, ensuring the church’s fragile Baroque art and living traditions endure for future generations.