Arraial Ferreira Neto

Introduction

Arraial Ferreira Neto in Tavira offers a rare window into the Algarve’s tuna fishing past. Established in 1943 to support seasonal fisheries, this former tuna village was carefully restored and now welcomes visitors as a heritage hotel and living museum. Exploring Arraial Ferreira Neto, we connect directly with the people and rituals that shaped the region’s maritime identity—a story of tradition, challenge, and renewal.

Historic Highlights

⚓ A Purpose-Built Tuna Village

Arraial Ferreira Neto in Tavira began in 1943 as a model fishing village, designed by engineer João Sena Lino. Built at Quatro Águas after the sea destroyed an earlier camp, it replaced makeshift accommodations with a thoughtfully laid-out, self-contained settlement. For three decades, it supported up to 150 fishing families each tuna season, making it far more than a simple processing plant—it was a vibrant, temporary community.

“O acampamento da tribo que vai arrancar aquela riqueza ao mar.”

— Diário de Notícias

⛪ Life, Faith, and Tuna Runs

The layout reflected Estado Novo ideals: an orderly mix of family homes, communal amenities, workshops, and the little chapel of Nossa Senhora do Carmo. Villagers gathered for annual blessing ceremonies, mixing reverence with hope for bountiful catches. Stories passed down tell of springtime processions—families singing along the sandy paths, celebrating the First Tuna Ceremony, a rare tradition carried on even under official restrictions.

🎣 Rise and Decline

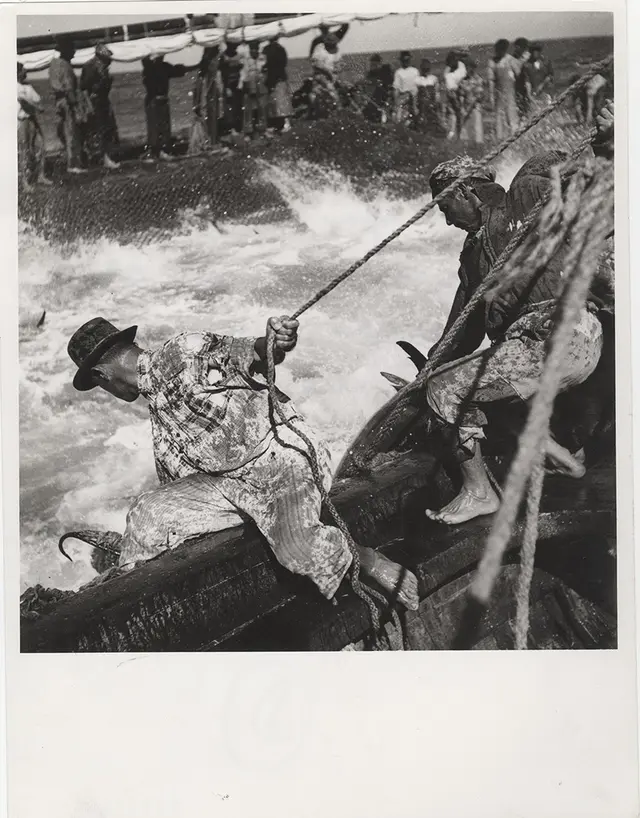

Daily life in the arraial danced to the rhythms of tides and migration. At dawn, crews set out for the almadrava—vast mazes of tuna nets—while women kept the communal bakery, children played at the school, and old-timers traded sea lore in the squares. In the 1950s, hundreds lived and worked here; tuna, though, proved as fickle as the sea. By the late 1960s, catches dwindled. In both 1970 and 1971, only one tuna was netted each year. By 1972, the village was abandoned—a ghostly place visited only by curious locals and memories.

“Once the tuna had disappeared, there was no reason for this part-time village to exist.”

— Becky in Portugal

🏨 Revival as Living Heritage

Decades later, Arraial Ferreira Neto rose from neglect, its architecture and spirit lovingly restored as the Vila Galé Albacora hotel. The fishermen’s huts became guest rooms, the bakery a tuna fishing museum displaying old nets, model boats, and rare photos. The chapel hosts events and quiet moments of reflection. Today, visitors can wander the same cobbled paths, listen to festival storytellers, or watch artisans demonstrate the art of “ronquear,” the expert butchering of tuna passed down for generations.

💡 Visitor Tip

Even if not staying at the hotel, stop at the onsite Tuna Fishing Museum—entry is free and the exhibits illuminate both daily life and dramatic changes that still shape Tavira’s heritage.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- 1943 – Arraial Ferreira Neto constructed at Quatro Águas, Tavira, replacing a storm-destroyed island camp.

- 1940s–1960s – Tuna fishing community thrives; hundreds live and work at the arraial each season.

- 1961 – Dramatic decline in tuna catches begins; industry viability falls.

- 1970–1971 – Only one tuna caught annually; operations become unsustainable.

- 1972 – Arraial Ferreira Neto abandoned as a fishing hub.

- 1980s–1990s – The site sits semi-derelict; recognized gradually as maritime heritage.

- 2000 – Restoration and adaptive reuse into Hotel Vila Galé Albacora and public museological center.

- 2002 – Classified as Imóvel de Interesse Público (Heritage Property of Public Interest).

Estado Novo Ideals and Tuna Villages

Arraial Ferreira Neto exemplifies Portugal’s mid-20th-century drive for modernized, self-sufficient “company towns” under the Estado Novo regime. Unlike organic fishing camps, this arraial was meticulously planned: homes, school, church, co-op, and factory together created a state-sanctioned model of communal labor and order. Through enforced hierarchy and paternalistic amenities, it mirrored broader corporatist trends in Portuguese industry, echoing similar settlements seen in mining or agricultural projects—but with a distinctly maritime flavor.

Architectural and Technical Synthesis

The settlement’s architecture blends rustic Algarve tradition with modern function: masonry walls, terra-cotta tile roofs, and painted azulejos join practical layouts and hygienic amenities. Reinforced concrete and vernacular materials produced a “rustic Portuguese” village that’s both charming and efficient. The partly walled compound, limited-access gates, and clear zoning reflect both the priorities of industrial efficiency and controlled community life shaped by the period’s ideologies.

Society, Ritual, and Everyday Life

Life at Arraial Ferreira Neto was deeply collective and shaped by rhythm: boats deployed for Atlantic bluefin, nets repaired onshore, families supporting one another. Religious ritual blended with labor—most notably the processions and blessings for the First Tuna Ceremony. The camp’s own chapel, school, bakery, and communal mess hall fostered a rich—though temporary—social fabric. Notably, stories survive of both triumph (years of abundant tuna) and hardship (the great empty seasons), passed down via families and now preserved in oral histories and local festivals.

Collapse, Memory, and Heritage Value

The arraial’s decline illustrates global shifts in fisheries and local economics: fewer tuna, environmental changes, and industry reorientation. Its sudden abandonment left it a poignant emblem of loss. Initially overlooked during Portugal’s post-1974 transformations, it later gained recognition as a rare industrial landscape, representing a vanished tuna world once central to the Algarve’s social and economic identity. The 2002 heritage listing secured its preservation, and its careful conversion into a heritage hotel exemplifies adaptive reuse—balancing tourism, cultural continuity, and conservation.

Comparative Perspective and Enduring Impact

While similar tuna villages existed, such as Arraial do Barril, few remain as intact or accessible as Arraial Ferreira Neto. Its Estado Novo-inspired design contrasts with the humble, organic growth of earlier camps, and its survival as a living heritage complex sets it apart. Nearby, the evocative Anchor Graveyard at Praia do Barril complements this legacy—rows of rusted anchors recalling the once-grand scale of Atlantic tuna fisheries. Culturally, Arraial Ferreira Neto remains a touchstone for local identity: annual festivals, gastronomy, and ongoing storytelling around the “gente do atum”—the tuna people—sustain its memory and relevance.

Source Foundations

The site’s history and significance are grounded in Portuguese heritage records (SIPA/DGPC), municipal archives, oral traditions, and published academic research. This multi-sourced approach corroborates key facts—dates, events, and architectural features—while ensuring that the lived realities, rituals, and local expressions endure alongside restored walls and public exhibitions.