Museo Nazionale Romano, Terme di Diocleziano

Introduction

The Museo Nazionale Romano, Terme di Diocleziano, brings Rome’s ancient Baths of Diocletian into daily life. Visitors can explore colossal ruins, marvel at Michelangelo’s adaptive architecture, and enjoy artifacts where emperors once mingled with citizens. Today, the vast spaces blend Roman innovation, Renaissance vision, and modern exhibits, making the Terme di Diocleziano a living testament to Rome’s enduring cultural spirit. Each visit lets us step into history—and see how it shapes our present.

Historic Highlights

🏛️ A New Age of Imperial Bathing

The Museo Nazionale Romano, Terme di Diocleziano, stands on the site of the largest public bath ever constructed in ancient Rome. Ordered by Emperor Maximian in honor of his co-emperor Diocletian, these thermae opened around AD 306. Their scale is breathtaking: more than 3,000 Romans could bathe here at one time, surrounded by elaborate halls, colossal columns, and gardens stretching over 13 hectares—nearly double the capacity of the famed Baths of Caracalla.

“A work of such magnificence to be given to the Roman people”—

— Dedication Inscription, Baths of Diocletian

🛁 From Ritual Bath to Cultural Hub

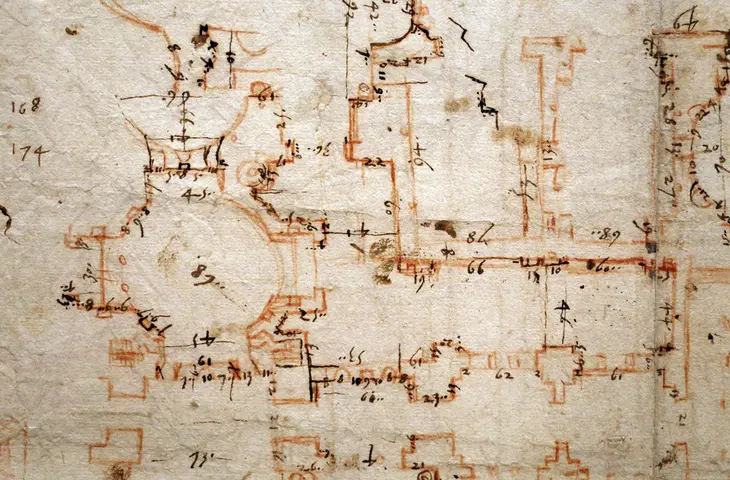

Inside, daily life bustled. Romans moved from the heated caldarium to the iconic frigidarium—now Santa Maria degli Angeli’s grand nave. Gymnasiums flanked each side, echoing with shouts from exercise or poetry readings. Libraries, lecture rooms, and even assembly spaces were part of the design. The baths weren’t just about hygiene; they formed a center for socializing, learning, and leisure. The site’s capacity arose from ingenious Roman engineering and state-of-the-art brickwork created solely for this project.

🧱 Transformation Across Centuries

After thriving for more than two centuries, the baths fell silent when the aqueducts were cut in 537 AD. Locals scavenged marble and metals, but legends grew. Some thought the vast ruins were a forgotten palace. Come the Renaissance, Pope Pius IV asked Michelangelo to transform the frigidarium into a church honoring Christian martyrs—preserving the ancient walls in a bold act of reuse. Today the basilica impresses with its vaulted ceiling and granite columns, blending imperial grandeur and spiritual serenity.

“Michelangelo embraced the ancient architecture, creating a church within the ruins.”

— Scholarly tradition

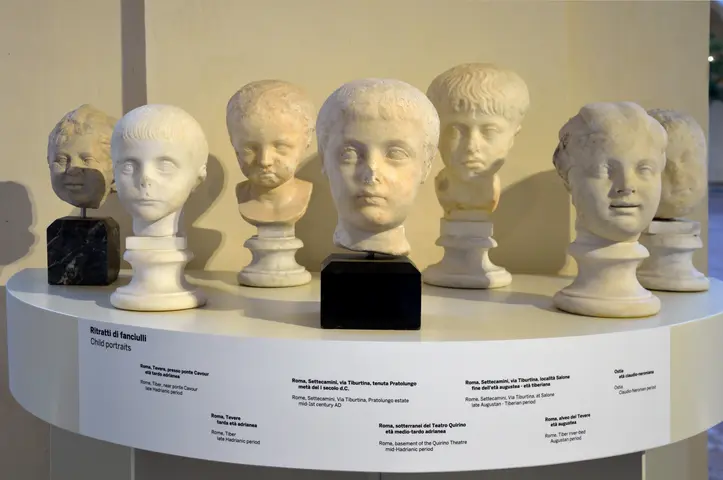

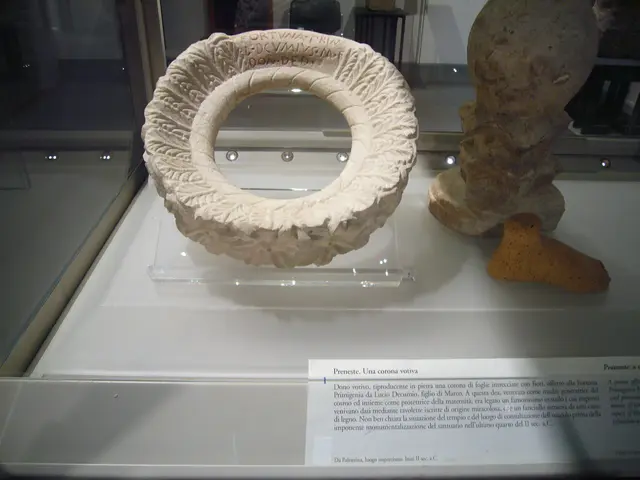

🎨 Living Heritage: From Monastery to Museum

The baths adapted with every era. The Carthusian cloister’s peaceful courtyards grew where athletes once trained. In the 19th century, the baths sheltered artists like Moses Ezekiel, who hosted famous Friday salons beneath ancient vaults. In 1889, the National Roman Museum opened here, displaying sculpture and inscriptions amid history-laden gardens. Special exhibitions—even a planetarium inside the Octagonal Hall—brought new life. Today, more spaces welcome the public, thanks to major restorations begun in 2023.

💡 Visitor Tip

Pair your visit with a peek into Santa Maria degli Angeli’s meridian line at noon—watch a sunbeam mark the calendar, linking ancient engineering, Renaissance faith, and scientific curiosity in one magical moment.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- AD 298— Baths of Diocletian commissioned by Maximian for Diocletian.

- AD 306— Baths completed and opened after Diocletian’s abdication.

- Early 5th c.— Major restorations; continued public use.

- AD 537— Aqueducts cut during Gothic War; baths abandoned.

- 7th c.— Christian church (San Cyriaco in Thermis) established in ruins.

- 1561— Pope Pius IV and Michelangelo convert frigidarium to Santa Maria degli Angeli; Carthusian monastery founded.

- 1702— Meridian line installed for Gregorian calendar at church.

- 1870— Baths site transferred to Italian state.

- 1889— Museo Nazionale Romano founded in the complex.

- 1911— International Archaeological Exhibition held; major restorations.

- 1928–1983— Octagonal Hall serves as Rome’s planetarium.

- 2023— Major museum restoration and re-opening of exhibit halls begun.

Imperial Ambition and Social Ritual

The Baths of Diocletian marked the zenith of Roman public architecture, both as a symbol of the Tetrarchy’s stability and as a daily hub for every segment of urban society. Commissioned during an era where grand works reinforced imperial legitimacy, the baths fulfilled an agenda of public benevolence—providing places not just for bathing, but for exercise, study, commerce, and community interaction. The use of new, state-produced bricks and an expanded water supply (by extending the Aqua Marcia) underline how tightly integrated the baths’ construction was with Rome’s social and economic machinery.

Adaptive Reuse: From Pagan Rome to Christian Renaissance

After their operational decline in the 6th century, the baths experienced new meanings. Medieval Romans imagined the immense ruins as Palaces or sacred sites, imbuing them with legend. In the Renaissance, adaptive reuse took on new life as Michelangelo transformed the frigidarium into the seat of Santa Maria degli Angeli. Michelangelo’s design philosophy was more than artistic; it was early conservation, preserving ancient grandeur through creative repurposing. This blend of reverence for antiquity and change shaped subsequent Roman—and European—approaches to heritage.

Cultural Memory and Local Identity

The baths’ layered history is inextricable from Rome’s own evolving identity. From the 16th-century Carthusians who cultivated scholarship in quiet cloisters, to the 19th-century artists like Moses Ezekiel whose salons attracted notables from across the globe, the baths have long provided sanctuary for creativity and contemplation. Their story is also a study in resilience: following war, depredation, and urban development, their vaults continue to echo with community activity. The complex not only frames the Piazza della Repubblica but inspired the name of Rome’s central train station—“Termini”—embedding antiquity into the daily life of modern Romans.

Architectural Innovation and Influence

The architectural solutions of the Baths of Diocletian—colossal cross vaults, efficient spatial planning, and multi-use halls—became archetypes for centuries afterward. The influence is evident in later Roman buildings such as the Basilica of Maxentius and in Beaux-Arts architecture abroad. A comparative lens shows how Diocletian’s design advanced over predecessors like the Baths of Caracalla by accommodating more users within a similar footprint, optimizing the use of concrete and vaulting. The bath’s legacy also echoes in its adaptive reuse: few ancient monuments in Rome have experienced such transformation while preserving so much of their core structure.

Stewardship and Modern Conservation

Since the 19th century, state stewardship and scholarly intervention have allowed the site not only to survive, but to educate and inspire new generations. The establishment of the Museo Nazionale Romano and periodic restorations demonstrate commitment to both preservation and dynamic public engagement. Recent projects, such as the 2023 initiative to open the “Seven Great Halls,” reflect a vision of making heritage accessible, relevant, and resilient in the face of challenges from urban life and climate. Each phase of reuse is grounded in careful research, combining archival documentation, archaeological evidence, and cultural memory to guide responsible conservation and interpretation.