Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica - Palazzo Barberini

Introduction

The Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica - Palazzo Barberini in Rome brings Baroque splendor, art, and history together. This exquisite palace tells the story of ambitious popes, celebrated architects, and lively gatherings under masterpieces of painting. Today, Palazzo Barberini welcomes us as a museum, offering a window into Rome’s grand past and vibrant present. Walk in, and you’ll discover layers of beauty, intrigue, and community in every hall.

Historic Highlights

🏛️ Origins of Palazzo Barberini

The Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica - Palazzo Barberini began as the Barberini family’s dream to leave their mark on Rome. Construction started in 1628, soon after Cardinal Maffeo Barberini became Pope Urban VIII. Three architectural giants—Maderno, Borromini, and Bernini—combined talents, producing a palace “the likes [of which] Rome had never before seen.” Far from a typical Renaissance palace, its open, H-shaped plan and grand loggia reflected Baroque ambition.

“What the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did.”

— Roman proverb on the family’s legacy

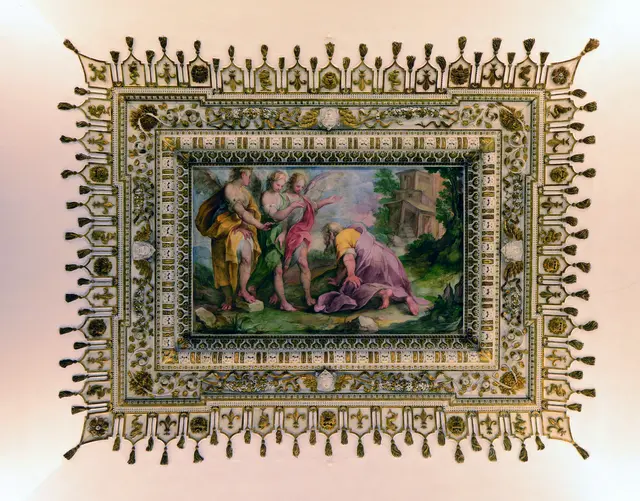

🎨 A Palace Full of Art & Invention

Palazzo Barberini dazzled not just through its design, but through artistic brilliance. Pietro da Cortona’s ceiling in the Gran Salone, bursting with gods, virtues, and the family’s bees, redefined Baroque illusionism. Lavish events filled the palace—operas, balls, debates. Bernini and Borromini’s staircases still impress: Bernini’s stately square stairs for show, Borromini’s elegant oval spiral staircase for private passages, washed in sunlight from above.

“As I entered the great hall, my breath caught at the sight of Divine Providence soaring above…”

— Imagined journal of a 17th-century apprentice

🐝 Folklore, Feasts, and Barberini Bees

The palace became a cultural hub, hosting power-brokers and creative spirits. Barberini bees, symbolizing industry and ambition, still decorate fountains and facades across the city. But the family’s reach stirred satire: Romans joked about the bees’ role in funding art—with bronze stripped from the Pantheon’s roof, earning them the infamous saying quoted above. The palace gardens once saw mock naval battles and open-air games, a spectacle for both elite and public alike.

🏛️ From Private Seat to National Museum

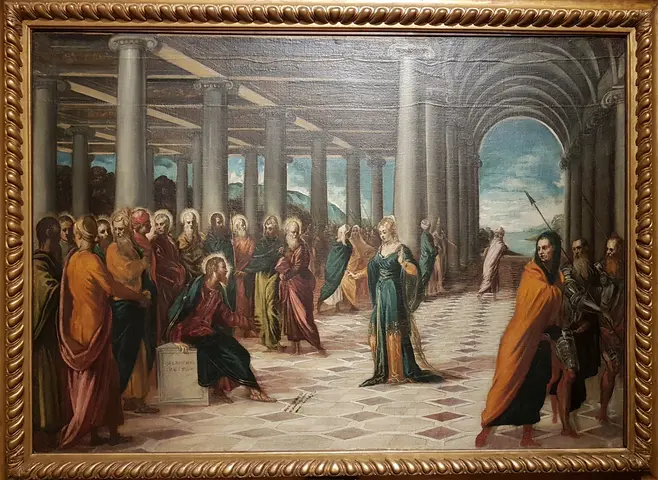

As time passed, fortunes faded and the palace saw less splendor. Pieces of its once-glittering art collection were lost to sales. Yet, in 1949, the Italian state acquired Palazzo Barberini to expand the National Gallery of Ancient Art. For decades, a military officers’ club stubbornly held part of the palace, creating an odd overlap of museum and private club. Only in 2010 was the palace fully opened to visitors, revealing its Baroque treasures in freshly restored galleries. Today, this Roman monument stands not only as a triumphal arch to the city’s past, but also as a bustling museum filled with masterpieces by Raphael, Caravaggio, and Holbein.

💡 Visitor Tip

Don’t miss Borromini’s spiral staircase—it’s tucked away, and a highlight of Roman Baroque engineering. Visit during a concert or special exhibit to experience the Gran Salone alive with music as it once was.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- 1623 – Cardinal Maffeo Barberini becomes Pope Urban VIII.

- 1625 – Barberini family acquires Sforza property on Quirinal Hill.

- 1628 – Construction of Palazzo Barberini begins.

- 1633 – Main structure largely completed; interior decoration continues.

- 1639 – Pietro da Cortona completes the Gran Salone fresco.

- 1671–1679 – Major remodelling and creation of ground-floor gallery.

- 1738 – Main Barberini line dies out; palace gradually declines.

- 19th century – Art collection dispersed; gardens reduced by new roads.

- 1949 – Italian state acquires Palazzo Barberini for the National Gallery.

- 2006–2010 – Officer’s Club vacates; full restoration and public opening.

Baroque Innovation and Urban Ambition

Palazzo Barberini’s construction marked a turning point in Roman palace design. The palace broke away from Renaissance models like Palazzo Farnese, embracing the Baroque ideals of movement, openness, and theatricality. The H-shaped plan catered to both city display and private retreat, and the monumental loggia offered a visible declaration of papal power. Borromini’s spiral staircase—flooded with natural light and decorated with the Barberini bee—is an emblem of Baroque technical virtuosity, influencing future generations of architects.

Cultural Policymaking through Patronage

The palace’s founders understood art as an instrument of political messaging. Pope Urban VIII channeled vast resources into architecture, commissioning artists like Pietro da Cortona to glorify the family’s papacy. Events staged at Palazzo Barberini—operas, poetry recitals, mock naval battles—wove the palace into Rome’s cultural life, blurring boundaries between elite festivities and public spectacle. These grand gestures bolstered the city’s reputation as a creative and intellectual center during the Baroque period.

Barberini Legacy: Art, Folklore, and Controversy

The Barberini’s triumphal ambitions are still visible in Rome’s built environment, from their Piazza to Bernini’s Triton Fountain. Yet their alleged abuses (notably the bronze removal from the Pantheon) fueled satire and skepticism. The phrase “Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini” encapsulates this complex legacy—a blend of pride in their artistic contributions and criticism for their methods. Local folklore, urban myths about ghostly theatres, and the recurring image of the bee all keep the palace alive in popular imagination.

Museum Era: Adaptation, Preservation, and Community

From the mid-20th century, Palazzo Barberini transitioned from private residence to public institution. The government prioritized conservation, adapting opulent Baroque rooms into secure art galleries. The protracted battle to reclaim the entire palace from a well-entrenched military club became a symbol of cultural perseverance; when rooms were finally opened to the public, Romans celebrated the “liberation” of their heritage. Ongoing restoration, robust climate controls, and a dedicated conservation lab reflect current challenges in balancing preservation with visitor engagement and environmental threats.

Comparison with Other Roman Palaces

Contrasted with “fortress-like” Renaissance palaces such as Farnese, Barberini’s architectural openness and inventive plan set the stage for later Baroque and Rococo palaces in Rome and beyond. Meanwhile, Palazzo Corsini (the National Gallery’s other home) illustrates a different chapter: its intact collection and 18th-century scale highlight changes in taste and collecting habits. Together, Barberini and its counterparts chronicle the evolution of Rome’s grand homes—each reflecting shifts in power, art, and society.

Sources and Research Rigor

This synthesis draws on archival Barberini documents, contemporary accounts, and scholarly monographs. Primary sources include 17th-century guidebooks and diaries detailing palace life. Secondary sources such as Cicconi’s study on Baroque power and architectural analyses by Marder offer critical interpretations. Museum and official reports verify recent restoration and usage, while local folklore and urban legends are tracked through oral histories and journalistic sources. The result is a narrative balanced between verified fact and cultural storytelling, honoring Palazzo Barberini’s enduring place in the Roman—and European—heritage landscape.