Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere

Introduction

The Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere welcomes us into Rome’s layered past, where ancient columns and glowing mosaics share stories over centuries. As one of the city’s oldest Marian churches, Santa Maria in Trastevere draws locals and explorers alike. Its familiar piazza, rich legends, and vibrant artistry make every visit a bridge between neighborly Trastevere life and the world’s cultural heritage. Let’s take a closer look at its remarkable history.

Historic Highlights

⛪ Origins and Earliest Legends

The Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere stands as Rome’s earliest church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Tradition holds it began as a house-church founded by Pope Callixtus I in the 3rd century, long before Christianity was legal in the Empire. According to local legend, a miraculous spring of oil—the fons olei—gushed from its site the night Christ was born, interpreted by Trastevere’s residents as a sign of the Messiah’s arrival.

“I prefer that it should belong to those who honor God, whatever be their form of worship.”

— Attributed to Emperor Alexander Severus

🏛️ Medieval Renewal and Artistic Splendor

In the 12th century, Pope Innocent II transformed Santa Maria in Trastevere into a new Romanesque basilica, asserting papal unity after a church schism. Ancient granite columns from the Baths of Caracalla were integrated, connecting imperial Rome to Christian purpose. The apse’s luminous mosaics from 1143 introduced a tender image of Christ and Mary, surrounded by saints and Pope Innocent himself, reinforcing both spiritual and political messages.

“Including one’s own portrait in a donor mosaic was a common medieval practice.”

— Medieval Mosaics

🎨 Baroque and Modern Layers

The 17th-century ceiling by artist Domenichino, gilded and painted with the Assumption of the Virgin, crowned the nave in Baroque grandeur. Architect Carlo Fontana reshaped the facade and portico in 1702, preserving the medieval mosaic of the Madonna and Child above the entrance. Nineteenth-century restorers, driven by enthusiasm for medieval style, relaid the Cosmatesque floor and even chiseled pagan faces off ancient capitals—an episode sparking debate among visitors and conservators alike.

🌍 Community and Living Traditions

SANTA Maria in Trastevere remains a living center for its neighborhood. The Madonna della Clemenza icon, paraded in medieval times to end drought or plague, still warms the hearts of locals today. Every Christmas, volunteers serve festive meals for Rome’s poor beneath the ancient columns, echoing the site’s tradition of care stretching back to its earliest days.

💡 Visitor Tip

Visit in the late afternoon when golden light sets the old mosaics aglow and sit quietly in the nave—locals say it’s the best way to sense centuries of stories woven into Trastevere’s heart.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- c. 220 CE – Pope Callixtus I founds the original Christian titulus; early house-church established in Trastevere.

- c. 340 CE – Pope Julius I constructs a larger basilica, now known as Titulus Iulii.

- 410 CE – Basilica is likely damaged during the Visigothic sack of Rome; repairs follow under Pope Celestine I (422–432).

- 8th century – Restorations under Pope Hadrian I; the church maintains its status in papal documents.

- 1140–1143 – Pope Innocent II rebuilds the basilica, adding Romanesque mosaics and columns.

- 1291 – Pietro Cavallini creates the famed mosaics depicting the Life of Mary under Pope Nicholas IV.

- 1617 – Domenichino designs and paints the ornate coffered ceiling.

- 1702 – Carlo Fontana remodels the facade and piazza; portico, statues, and fountain enhancements added.

- 1860 – 19th-century restoration by Virginio Vespignani aims for a medieval revival, replacing floor and wall decoration.

- 2018 – Major facade and mosaic conservation completed.

- 2020 – Modern lighting system installed to protect and showcase artworks.

From Titulus to Icon: Early Christian Roots

The basilica’s foundation in the third century, anchored in primary sources like the Liber Pontificalis, marks Santa Maria in Trastevere as a rare witness to Christianity’s transition from private devotion to public institution. Its contested status as Rome’s first Marian church, preceding the Council of Ephesus (431), underscores the site’s theological importance before Marian veneration became widespread. Artefacts such as reused columns tie the church to late imperial Rome’s practice of spolia, reflecting both practical and symbolic appropriation of antiquity.

Papal Schism, Power, and 12th-century Renewal

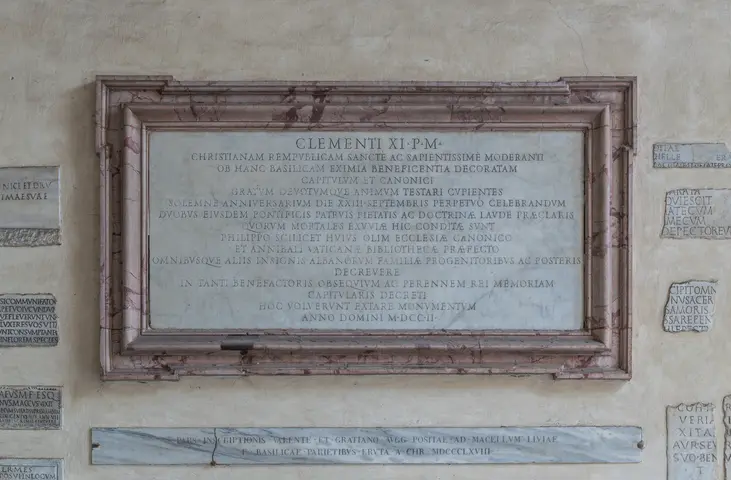

The high medieval era brought drama and transformation. Following the 1130 papal schism, Innocent II’s decision to demolish and rebuild the basilica was deeply political—a visible claim to legitimacy over the defeated antipope Anacletus II, whose burial in the church was intentionally erased. The architecture, using columns from the Baths of Caracalla and iconography new to Rome (Mary as Queen of Heaven), blended innovation with continuity. Inscriptions recorded by Forcella, coupled with stylistic studies by Kinney, reveal how the building functioned as a visible statement of restored papal order.

Mosaic Artistry and the Rise of Local Devotion

Through the 13th century, mosaic cycles by Pietro Cavallini helped define a new naturalism and Marian narrative in sacred art—seen as transitional between Byzantine influence and the Italian Renaissance. The inclusion of local legends, like the fons olei in Cavallini’s Nativity, linked larger Christian history to Trastevere’s communal memory, as seen in academic analysis by Lidova and Medieval Mosaics. Mosaics thus served both as catechism and identity rituals for the local populace.

Evolving through Baroque and Nineteenth-century Restoration

Renaissance and Baroque adaptations, notably Domenichino’s ceiling and Fontana’s facade, illustrate layered approaches to preservation—each era leaving its mark without erasing earlier periods. The 19th-century “medieval revival” under Vespignani, shaped by scholarly romanticism, strove to recover an idealized past, sometimes with irreversible choices such as stripping ancient capitals of pagan images. These restoration philosophies, debated in Kinney’s research, show the shifting values from Baroque grandeur to historical authenticity.

Contemporary Preservation and Community

In the face of modern threats—pollution, climate change, mass tourism—recent conservation pairs advanced technology (e.g., climate-control for the Madonna della Clemenza) with respect for the basilica’s palimpsest character. Studies by Figliola et al. highlight passive climate strategies rooted in traditional design, while conservation reports detail sensitive integration of modern infrastructure. Community participation, from local devotional practice to global tourism and Sant’Egidio’s social outreach, ensures that the basilica remains a living monument: historically layered yet ever responsive to present needs.

Comparative Perspective

In relation to sites like Santa Maria Maggiore and San Clemente, Santa Maria in Trastevere stands out for its continuous role in community life and its harmonious architectural layering. While its peers may boast greater papal patronage or accessible archaeological layers, Trastevere’s basilica weaves local folklore, social function, and art into a uniquely resilient whole—mirroring Rome’s own history of adaptation and renewal.