Santa Maria in Aracoeli Basilica

Introduction

Santa Maria in Aracoeli Basilica crowns Rome’s Capitoline Hill, inviting us to discover layers of history, legend, and devotion. Once the gathering place of senators and saints, this Roman monument remains vibrant in the city’s everyday life. Whether you’re drawn by art, folklore, or panoramic views, Santa Maria in Aracoeli connects ancient and modern Rome in a way few churches do. Its doors are wide open for curious souls.

Historic Highlights

🏛️ From Roman Temples to Christian Sanctuary

Santa Maria in Aracoeli Basilica sits atop what was once the Temple of Juno Moneta, hinting at its layers of history. Beneath the church, archaeologists have found traces of both a Roman apartment building and an elite townhouse, buried when the medieval basilica rose above them. According to tradition, Pope Gregory the Great founded the first church here in the 6th century, when Rome was still feeling the influence of Byzantium.

“The Senate voted to consecrate an altar to Pax Augusta… in the Campus Martius.”

— Augustus, Res Gestae

✝️ Civic Church and Franciscan Renewal

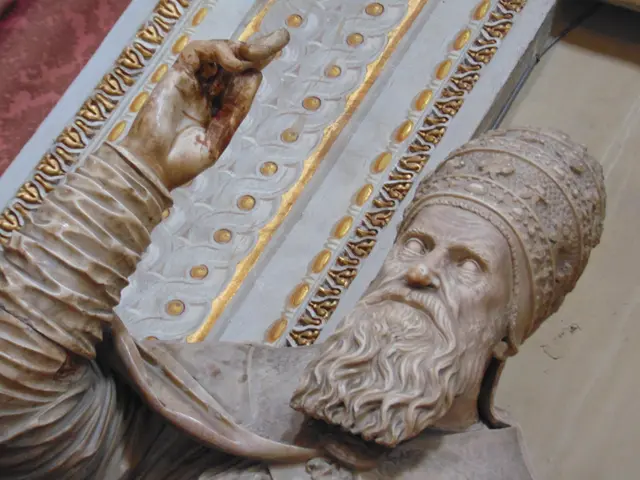

Aracoeli became Rome’s civic church in the 12th century, hosting assemblies and shaping the city's political life. The Roman commune, rebelling against papal power, made it their spiritual home. In 1250, Pope Innocent IV entrusted the church to the Franciscans, who rebuilt it with Romanesque-Gothic charm and an eclectic mix of ancient columns. The iconic Cosmatesque marble floor and the massive staircase of 124 steps—built in 1348 as a vow during the Black Death—still impress visitors and devotees alike.

“The people of Rome, grateful for deliverance from the plague, built this stairway to honor the Virgin.”

— Inscription at Aracoeli’s entrance

🎨 Legends, Art, and Living Devotion

Santa Maria in Aracoeli glows with treasures: Pinturicchio’s late 15th-century frescoes, a Donatello tomb slab, and its shimmering 16th-century coffered ceiling commemorate the victory at Lepanto. The fabled Santo Bambino statue—carved from Gethsemane olive wood—remains at the heart of local miracles and Christmas pageants. Romans once summoned the statue to the sick; even after it was stolen in 1994, prisoners wrote open letters pleading for its return, showing the basilica’s meaning across all walks of life.

⛲ A Place of Ritual and Social Connection

Climbing the grand staircase is an age-old Roman ritual—some still ascend on their knees, praying for a child or a stroke of luck. In the 17th century, wealthy locals even rolled barrels of stones down the steps at night to dislodge sleeping vagrants, a colorful reminder of the basilica’s role in both charity and social drama. The bells once set the city’s rhythm, marking the hours for centuries.

💡 Visitor Tip

Pair a visit to Santa Maria in Aracoeli with a stroll through the neighboring Capitoline Museums, then pause on the steps for sweeping city views. Watch for the Madonna mosaic above the central door—a tiny survivor of lost medieval splendor.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- 6th century – Foundation of the first church, possibly under Pope Gregory the Great.

- 12th century – Santa Maria in Capitolio confirmed as Benedictine abbey of civic importance.

- 1250 – Pope Innocent IV grants the church to the Franciscans.

- 1285–1291 – Consecration of the new Romanesque-Gothic basilica.

- 1348 – Construction of the monumental staircase as a thanksgiving for the end of the Black Death.

- 1486 – Pinturicchio frescoes the Bufalini Chapel.

- 1571–1575 – Naval-votive coffered ceiling added after the victory at Lepanto.

- 1797 – Church desecrated during Napoleonic occupation, later restored.

- 1880s–1910s – Demolitions for the Vittoriano monument change Aracoeli's urban setting.

- 1948 – Rome consecrated to Mary by Pope Pius XII at Aracoeli.

Origins and Transformation

Santa Maria in Aracoeli’s history is deeply layered, starting atop the Capitoline’s ancient religious heart. The site’s shifting role—from pagan temple to Christian sanctuary—mirrors broader patterns of continuity and adaptation in Rome. Archaeological investigations have confirmed Roman houses and temples once stood here, while documentary evidence points to a 6th-century Christian foundation. This early phase, influenced by Byzantium, set a precedent for the site as a locus of spiritual power.

Civic Sanctuary and Franciscan Leadership

The basilica’s use by Rome’s medieval commune signified the blending of sacred and civic life. By hosting assemblies and elections, Aracoeli became more than a parish; it embodied the city’s republican aspirations and served as the symbolic “chapel” of the Roman people. The Franciscans’ stewardship, granted by papal decree in 1250, marked a new chapter—the Order rebuilt and expanded the church, infusing it with their characteristic simplicity and devotion. Their Cosmatesque floors and spolia columns reflected a deliberate reuse of antiquity, visually linking Christian and Roman heritage.

Art, Ritual, and Urban Identity

Aracoeli’s artistic patrimony is both rich and idiosyncratic. While wall paintings by Pinturicchio and floor tombs by Donatello connect it to Renaissance and humanist traditions, features such as the wooden coffered ceiling recall collective victories, specifically the 1571 Battle of Lepanto. The basilica’s role in rituals—hosting poetic coronations, victory celebrations, and the veneration of icons like the Madonna Advocata—cements its status as a spiritual and civic heart of Rome. Local legend also enlivens its history: Augustus’s visage of the Virgin, while apocryphal, is a cherished narrative that ties Aracoeli to Rome’s imperial and Christian destinies.

Architectural and Social Continuities

The church’s architecture is noteworthy for its resistance to Baroque overhauls found elsewhere in Rome, allowing its medieval structure and Romanesque-Gothic style to remain largely intact. Sparse but significant Renaissance and Baroque modifications—such as the 16th-century marble portal or 17th-century ceiling—show a pattern of enhancement rather than replacement. The basilica’s staircase, built after the Black Death, acquired meaning through use. Ordinary Romans, noble families, soldiers, and even beggars gave the site social resonance; anecdotes involving Penitents, street dwellers, and civic leaders are woven into its marble steps and nave.

Cultural Significance and Survival

More than an architectural relic, Aracoeli endures as a living institution. Its symbolic role as “the people’s church” persists, underscored by annual city council ceremonies and Christmas events centered around the Santo Bambino. The basilica’s fate during times of upheaval—sacral desecration under Napoleon, near-demolition for the Vittoriano, heritage restoration campaigns—illustrates the challenges and resilience inherent to historic urban sites. Conservation efforts today are shaped by environmental concerns, funding needs, and the ongoing commitment of both authorities and local devotees.

Comparative Perspective

Placed alongside other Roman and Italian basilicas—such as Santa Maria in Trastevere or Florence’s Santa Croce—Aracoeli stands apart for its entwinement with civic identity and municipal functions. While sharing architectural forms and artistic splendors, only Aracoeli bridges ancient and medieval Rome with such clarity, serving as a touchstone for both the city’s self-image and the continuity of tradition through centuries of transformation.