Galleria Doria Pamphilj

Introduction

The Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome is far more than an art-filled gallery; it’s a living palace telling five centuries of family, history, and culture. Nestled on bustling Via del Corso, this Roman monument lets us step inside grand halls, Baroque galleries, and quiet courtyards where popes, princes, and everyday Romans crossed paths. Join us as we uncover the stories, legends, and beauty that make this site a cultural treasure.

Historic Highlights

🏰 Renaissance Roots

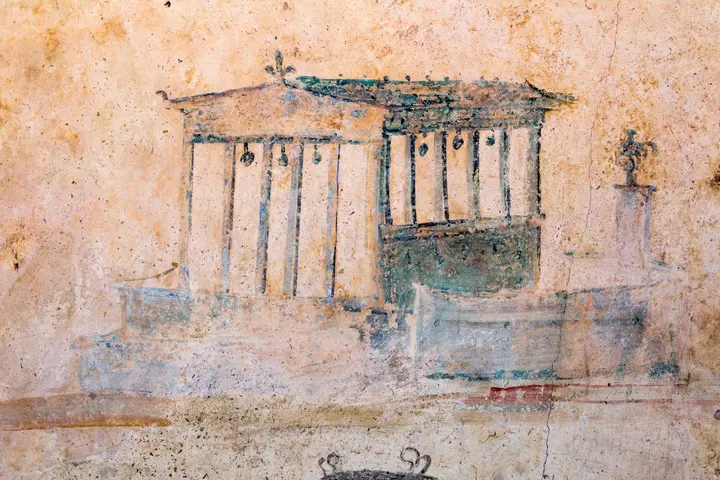

The Galleria Doria Pamphilj stands at the heart of Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, whose story began in the early 1500s. Originally built for Cardinal Fazio Santoro, its elegant courtyard remains a testament to the High Renaissance—a style that shaped much of Rome’s historic center. The Della Rovere family, with ties to Pope Julius II, briefly called it home, adding to the residence’s rich lineage of Rome’s elite.

🏛️ The Baroque Transformation

The palace’s true Baroque glory unfolded when the Pamphilj family took over in the 17th century. Pope Innocent X’s nephew, Camillo Pamphilj, inherited the mansion through his marriage with Olimpia Aldobrandini in 1647 and began an ambitious expansion. Architect Antonio Del Grande unified a maze of old structures and created grand staircases, while the interiors gleamed under Baroque artists like Pietro da Cortona.

“Del Grande’s task was to consolidate the patchwork of earlier additions into an ‘organic and rational structure’.”

— Leone, JSAH (2004)

🖼️ Art, Legends & Living Heritage

By the 18th century, architect Gabriele Valvassori gave Palazzo Doria Pamphilj the refined Baroque façade and spectacular mirrored galleries we stroll today. Inside, floor-to-ceiling paintings—including masterpieces by Velázquez—stun visitors. Local legend holds that Pope Innocent X, upon seeing his starkly realistic portrait, declared:

“È troppo vero!” (“It’s too true!”)

— on Velázquez’s portrait

The gallery’s halls echo with tales of haunted ‘ladies in black’, mummified saints, and hidden statues, blending myth with daily life. During Rome’s carnivals, the Pamphilj family once watched festivities from their famed balconies—moments that colored memories for ordinary Romans and nobility alike.

💡 Visitor Tip

Explore the Gallery’s Hall of Mirrors in the late afternoon light for breathtaking reflections—and don’t miss the quirky cat statue perched above Via della Gatta: a playful piece of local folklore tied to hidden treasure tales.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- c. 1505–1507 – Cardinal Fazio Santoro builds the original Renaissance mansion.

- 16th century – Della Rovere family owns the palazzo.

- 1601 – Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini purchases and expands the residence.

- 1644 – Giovanni Battista Pamphilj becomes Pope Innocent X.

- 1647 – Olimpia Aldobrandini marries Camillo Pamphilj; palazzo passes to Pamphilj line.

- 1654–1666 – Major Baroque expansion under Camillo Pamphilj and architect Antonio Del Grande.

- 1730–1735 – Gabriele Valvassori builds the monumental Via del Corso façade and great gallery.

- 1767 – Major interior refurbishments for royal wedding of Andrea IV Doria Pamphilj Landi.

- 19th century – Completion of Via della Gatta wing and integration of rental apartments.

- 20th–21st centuries – Palace remains private, opens gallery to the public; extensive conservations continue.

Urban Evolution & Architectural Styles

The Palazzo Doria Pamphilj’s development mirrors Rome’s shift from Renaissance harmony to Baroque dynamism and later Rococo. Its earliest core, centered around Santoro’s courtyard, showcases Bramantesque arches—an enduring example of early 16th-century design. Later expansions under Aldobrandini and then Pamphilj families reveal how aristocratic ambitions and alliances shaped the city’s urban and social landscape. With each family, the palace morphed architecturally, reflecting not just personal tastes but broader shifts in Roman trends. The 17th-century Baroque expansions—guided by top architects such as Del Grande and advised by luminaries like Borromini and Pietro da Cortona—integrated previously scattered structures, placing theatrical emphasis on circulation, grand entrances, and art-filled galleries. The final 18th-century touches by Valvassori aligned the palace with European aristocratic aesthetics, capped by the mirrored gallery reminiscent of Versailles.

Patronage, Politics, and Art

Palazzo Doria Pamphilj’s evolution cannot be separated from Rome’s papal history. As popes, cardinals, and nobility reshaped the building, their motives spanned from self-glorification to fostering artistic innovation as a symbol of power. The union of Pamphilj and Doria lines through marriage merged political and financial capital, ensuring the family’s status atop Rome’s elite. The palace’s legendary art collection, assembled as both private delight and public display, serves as a snapshot of Italian noble connoisseurship. Masterpieces by Titian, Caravaggio, Velázquez, and others were judiciously kept in situ, embodying the aristocratic tradition of art as both prestige and patrimony.

Socio-Cultural Integration & Local Lore

Over centuries, Palazzo Doria Pamphilj became more than architecture—it was a living participant in the civic, cultural, and economic life of Rome. The palazzo’s balconies, carnival festivities, and employment of generations of locals wove it into the urban fabric. The transition of its owners from feudal patrons to figures like Prince Filippo Andrea Doria Pamphilj, the anti-fascist mayor of Rome, illustrates aristocratic adaptation to change, while oral traditions such as the ‘Lady in Black’ and relic veneration kept personal histories alive. Unique neighborhood features—like the famed cat statue on Via della Gatta—show how even sculptural details fostered ongoing local identity and stories.

Comparative Context & Cultural Legacy

When compared with other Roman palazzi such as Barberini and Colonna, the Doria Pamphilj’s layered development, hybrid architecture, and continued private stewardship stand out. Unlike state-owned counterparts, its gallery and halls remain curated by descendants, offering rare continuity and authenticity. The palace’s integration of Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo spaces within one block allows scholars and visitors to witness both artistic evolution and a living tradition of preservation.

Conservation & Contemporary Relevance

Modern preservation at Palazzo Doria Pamphilj exemplifies the challenge of balancing public access, private ownership, and heritage conservation. Environmental risks, urban pressures, and the cost of caring for centuries-old art require both technical innovation and financial creativity. Thanks to family initiatives, public programming, and adherence to heritage laws, the gallery remains one of Rome’s most intact noble residences open to all. Ongoing education and cultural events reinforce its relevance—not as a relic, but as a vibrant bridge between Rome’s aristocratic past and its shared future.