Basilica of Saint Mary of Minerva

Introduction

The Basilica of Saint Mary of Minerva in Rome reveals surprises to anyone who steps inside its unassuming façade. As we enter, star-flecked Gothic vaults arch overhead and tales of saints, scholars, and artists come alive. This unique Roman monument connects ancient temples, medieval friars, Renaissance masterpieces, and living communities—making Santa Maria sopra Minerva a must-visit for cultural explorers, educators, and history fans alike.

Historic Highlights

🏛️ From Temple to Basilica

The Basilica of Saint Mary of Minerva sits atop the remains of temples once dedicated to Minerva and Isis. In the eighth century, Pope Zachary built a small oratory here, welcoming Basilian nuns fleeing Constantinople. Their worship foreshadowed centuries of change, as ancient ruins gave way to one of Rome’s most vibrant churches.

“Christianized” the site by establishing a small oratory dedicated to the Virgin Mary, offering it to Greek-rite Basilian nuns who fled Constantinople.

— Masetti, 1855

⛪ Gothic Ambitions: The Dominican Era

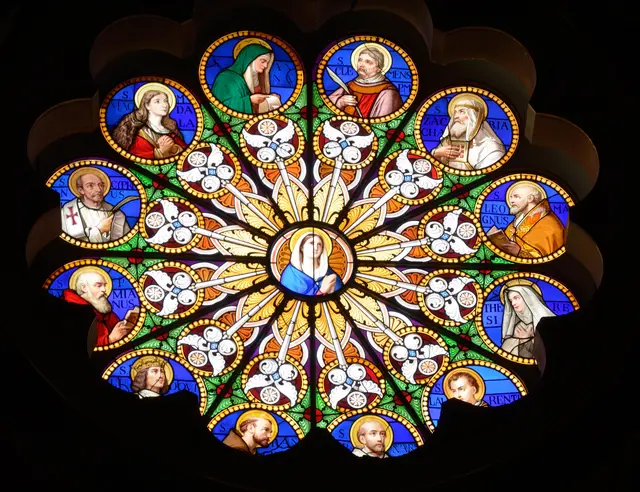

By 1280, Dominican friars began building today’s basilica, introducing the French/Tuscan Gothic style to Rome with pointed arches and ribbed vaults. Designed by Fra Sisto Fiorentino and Fra Ristoro da Campi, the construction was funded by popes and donors but progressed slowly, culminating in consecration in 1370. Unlike most Roman churches, Santa Maria sopra Minerva kept its medieval character—making it the city’s only true Gothic church.

🎨 Renaissance and Baroque Layers

Over centuries, the basilica blended Gothic bones with Renaissance and Baroque elements. Notable patrons included Cardinal Torquemada in 1453, who advanced the vaulting and façade, and Carlo Maderno, who enlarged the apse in 1600. Whenever you walk beneath the blue, starry ceiling, you’re tracing the artistic footsteps of Michelangelo—his "Christ Carrying the Cross" stands near the altar—and Filippino Lippi, whose Carafa Chapel frescoes remain vibrant.

“A restrained, plain façade that belies the Gothic interior behind it— a point often noted by visitors…”

— Arte.it, 2020

🕯️ Sanctuary of Saints and Stories

The basilica has long served the community—especially as the resting place of St. Catherine of Siena, Italy’s co-patroness. Every year, Sienese pilgrims visit her tomb under the altar. According to a favorite legend, her Sienese followers once smuggled her head past guards by transforming it, with her intercession, into rose petals. The church is also known for Bernini’s Elefantino: the whimsical elephant with an Egyptian obelisk in the piazza, said to aim its rear at the Dominicans’ door as a playful jest.

💡 Visitor Tip

Don’t miss the tranquil cloister’s frescoes, newly opened for visits. End your day with a coffee in the piazza—under the gaze of Bernini’s elephant and the church’s timeless façade.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- 8th century – Pope Zachary builds a small oratory at the site for Basilian nuns.

- 1255–1279 – Site transitions to Dominican friars; confirmed by Aldobrandino Cavalcanti.

- 1280–1370 – Construction of the present Gothic basilica begins and is consecrated.

- 1431, 1447 – Papal conclaves elect Eugenius IV and Nicholas V at the Minerva.

- 1453–1725 – Renaissance and Baroque architectural modifications made to interior and façade.

- 1557, 1566 – Elevated to titular church and minor basilica.

- 1633 – Galileo Galilei recants before the Inquisition at the convent.

- 1848–1855 – Major Neo-Gothic restoration under Fr. Girolamo Bianchedi.

- 2019–2020 – Comprehensive restoration preserves art and structure.

From Pagan Roots to Christian Heritage

Santa Maria sopra Minerva stands as the inheritor of a multi-layered past. Its foundation on ancient temple ruins is emblematic of early medieval Rome’s transition: as the papacy took root, pagan spaces were repurposed for Christian worship. Pope Zachary’s dedication of the site to Basilian nuns reflected not only the city’s religious evolution but also the transmission of Eastern spiritual traditions into the Western church. This early phase remains sparsely documented, but the symbolic choice to build “above Minerva” mapped new meaning atop old stones.

Dominicans and the Gothic Leap

The basilica’s transformation in the late 13th century signalled a turning point for both Rome and the Dominican Order. The friars, expanding their intellectual and urban ministries, introduced Gothic architecture—a style at odds with Rome’s classicism. Architects Fra Sisto and Fra Ristoro modeled the church after Santa Maria Novella in Florence, producing features rarely seen in the city: pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and colored glass. The church’s ‘insular sapientiae’ (island of wisdom) identity flourished as Dominicans educated clergy and laity alike, helping Rome become a center of Catholic scholarship that would influence Europe for centuries.

Political, Artistic, and Scientific Crossroads

Soon, Santa Maria sopra Minerva became central to Rome’s civic and political life. The fortified convent hosted two 15th-century papal conclaves during times of unrest, offering a secure base away from the volatile Lateran. Its walls sheltered saints—like Catherine of Siena—and statesmen, while its altars honored noble families and guilds. The basilica’s Renaissance and Baroque layers—funded by papal and cardinal patronage—brought new art and architectural styles, blending old with new. Notably, the church also played a role in one of European history’s greatest intellectual showdowns: during the 17th century, the adjoining convent served as headquarters for the Roman Inquisition, forcing Galileo Galilei to abjure his theories within its chambers—a flashpoint in the perennial debate between science and authority.

Restoration, Folklore, and Local Identity

The basilica did not escape 19th-century trends in conservation. Seeking to revive a ‘medieval’ atmosphere, Fr. Bianchedi’s restoration erased many Baroque elements and introduced starry vaults and vibrant neo-Gothic frescoes. Such interventions, though controversial, preserved the basilica’s distinctiveness in a city more famous for Baroque and Renaissance monuments. Meanwhile, local legends—like the playful tale of Bernini’s elephant and the relic-smuggling of St. Catherine—wove Santa Maria sopra Minerva ever more deeply into Rome’s living folklore, its piazza a symbol of conviviality and resilience.

Modern (and Ongoing) Relevance

After years of political instability and expropriation, the Dominicans remain present, coexisting with the state to care for the monument. The basilica is a living religious, cultural, and economic resource: a place of daily worship, education, and pilgrimage; a destination for art lovers, musicians, and scholars; and an engine for local commerce. Recent restoration campaigns—culminating in the 2019–2020 work—testify to an ongoing partnership between heritage authorities and the church, with climate and environmental challenges ever in mind. Today, Santa Maria sopra Minerva is not just a monument, but an active stage for ritual, memory, and storytelling—where every stone, star, and statue speaks to Rome’s layered past and living present.