Arch of Titus

Introduction

The Arch of Titus in Rome rises at the edge of the Roman Forum, greeting visitors with its storied marble and powerful narrative. Built soon after 81 AD, this triumphal arch celebrates Emperor Titus’s deification and his victory in the Jewish War. Today, the Arch of Titus is a symbol of Roman achievement, cultural intersection, and deep historical memory, connecting us across centuries through art, ritual, and resilience.

Historic Highlights

🏛️ A Monumental Beginning

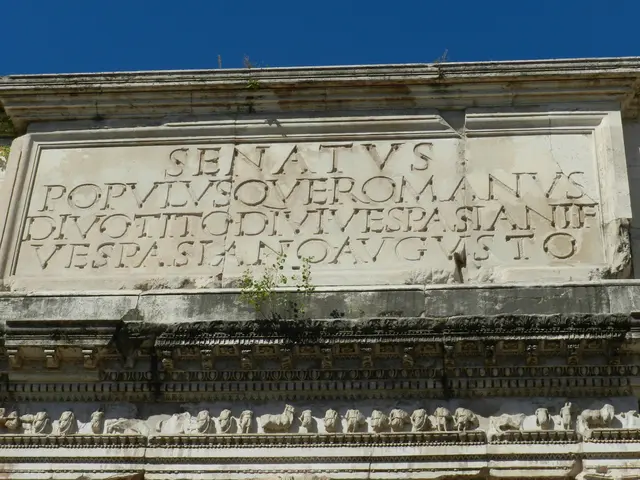

The Arch of Titus in Rome stands at the summit of the Via Sacra, marking both a ceremonial gateway and an enduring memorial. Created by order of Domitian, Titus’s brother, it honors not only a military triumph but the late emperor’s transformation into a god. The arch’s inscription, still visible today, identifies it as dedicated to the “deified Titus.”

“The Senate and People of Rome [dedicated this] to the deified Titus Vespasian Augustus, son of the deified Vespasian.”

— Attic Inscription, Arch of Titus (CIL VI, 945)

🎉 The Spoils of Jerusalem

What sets this Roman monument apart are its sculpted reliefs inside the vault. One panel shows Roman soldiers parading treasures looted from Jerusalem, including the famous seven-branched menorah. Another scene celebrates Titus’s apotheosis, with his soul depicted rising heavenward on an eagle’s back—melding statecraft and divinity. These lively carvings not only recorded a moment of victory, but also shaped centuries of collective memory. For generations, Rome’s Jewish community avoided walking under the arch, viewing it as a bitter reminder of exile. Yet on December 2, 1947, after the announcement of a Jewish state, the Chief Rabbi led worshippers under the arch—backwards—to symbolically undo the ancient humiliation.

“History’s reversal” — so eyewitnesses described the community’s bold crossing in 1947.

— Fellowship Blog, 2018

🏗️ Layers of Time and Restoration

For over 1,900 years, the Arch of Titus has seen Rome transform. At one point, it was absorbed into a medieval fortress and renamed the “Arch of the Seven Lamps,” its menorah carving inspiring both awe and legend. During the 1800s, the structure was saved from collapse by Giuseppe Valadier, who restored it using new travertine to distinguish ancient from modern masonry. Some locals lamented the loss of its romantic decay, but the careful restoration paved the way for modern conservation. In 2025, new scaffolding and expert hands again tend to the arch, ensuring the story can be passed on.

💡 Visitor Tip

To truly appreciate the reliefs, try visiting early in the morning or late afternoon when the low sun brings the carvings to life—look for the menorah and the triumphant figures in the shadows.

Timeline & Context

Historical Timeline

- 70 AD – Titus leads Roman forces in the sack of Jerusalem; Temple treasures seized.

- 81 AD – Titus dies; Domitian becomes emperor.

- Early 80s AD – Arch of Titus constructed atop the Via Sacra.

- 11th–12th centuries – Arch incorporated into Frangipane fortress; called “Arch of the Seven Lamps.”

- Early 19th century (1821–1823) – Major restoration by Valadier under Pope Pius VII.

- 2000–2001 – Conservation project addresses pollution damage and iron corrosion.

- 2025 – New conservation phase underway.

Imperial Propaganda and Deification

The Arch of Titus embodies a carefully crafted message of power and legitimacy. Built shortly after Titus’s death, its reliefs and dedication inscription secured his divine status and broadcasted Flavian authority to every passerby. Domitian seized upon his brother’s victory in the Jewish War to unite military success with the lineage’s claim to Rome. The monument functioned as both a memorial and a tool of political messaging that would set a precedent for subsequent Roman emperors.

Architectural Innovation and Influence

Architecturally, the arch introduced the Composite order in monumental form, influencing Western design for centuries. Its harmonious proportions, vivid reliefs, and original inclusion of marble and bronze statuary inspired some of the greatest works of the Renaissance and Neoclassical periods. Alberti’s church of Sant’Andrea in Mantua and the Arc de Triomphe in Paris both draw from the vocabulary debuted at the Arch of Titus. Even 19th-century restoration methods—anastylosis, or careful re-assembly—set standards still followed today.

Multi-Layered Significance and Community Memory

The monument’s significance evolved over centuries. In antiquity, it marked imperial power and divine favor. During the Middle Ages, it became part of local infrastructure and folklore, with its menorah carving giving rise to legends and its stones sheltering fortress inhabitants. For the city’s Jewish community, the arch was a living reminder of suffering and resilience, culminating in the community’s symbolic crossing in 1947 upon the creation of Israel. The menorah carved on the arch, once a symbol of loss, is now Israel's official emblem—a poignant example of historical transformation.

Preservation and Modern Challenges

Centuries of pollution, neglect, and earlier restoration materials (such as iron clamps) have posed ongoing risks to the Arch of Titus. Deterioration from acid rain and shifting blocks demanded both emergency measures and careful intervention. The blend of ancient marble and Valadier’s 19th-century travertine makes the arch a layered artifact, revealing choices and philosophies from different eras. Modern conservation maintains this balance, protecting both old and new elements. Current projects address issues such as biological growth and material stress, using minimal intervention and reversible techniques to honor authenticity.

Comparative Perspective and Legacy

Compared to the Arches of Septimius Severus and Constantine, the Arch of Titus set the standard for single-bay triumphal arches and personal commemoration. Its form and iconography echo through architectural history, while its intimate tie to both state power and personal fate distinguish it among Rome’s monuments. Each later emperor and generation re-interpreted, restored, or incorporated the arch into the fabric of Rome, ensuring its presence in civic pride, religious memory, and world heritage.